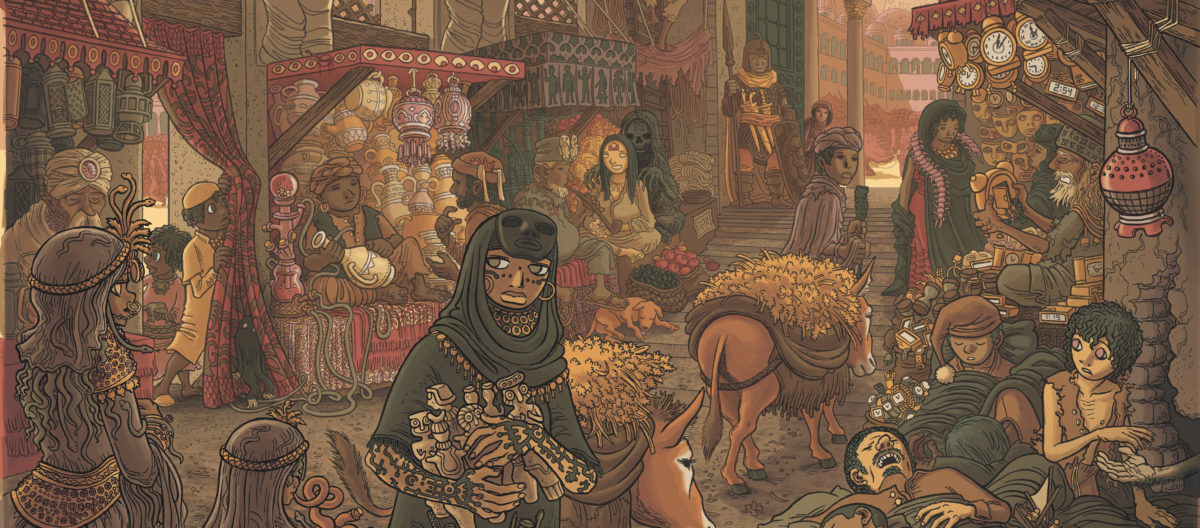

Should modern technology exist in Dreamland? In Dunsany and Lovecraft’s stories, Dreamland is implicitly a Medieval place, in keeping with both writers’ love of the past, and the general tropes of the fantasy genre. (You could even say it’s pre-Medieval: Dunsany’s stories and Lovecraft’s The Doom That Came to Sarnath feel like Orientalised images of the Axial Age and Bronze Age, of the time when mythologies and great religious texts were first written down.) For Dunsany especially (as for J.R.R. Tolkien), the pre-industrial past was an idealized world of farms and pastures, a harmonious place of green nature free of pollution, factory labor and other modern blights.

In the spirit of this, Dreamland by default is a fantasy mirror of the past. Some cultures have modern or even futuristic technology, but it’s rare. A low-tech, pseudohistorical feel doesn’t mean that Dreamland societies need to be regressive; firstly, it’s a fantasy, and secondly, going back in time can mean taking inspiration from cultural models that value different things, such as communal or matriarchal cultures and societies acknowledging nonbinary gender, as much as from cultures of slavery and monarchy.

But despite the fun of playing in the past, it would be limiting to say that Dreamland can only be about the past. Clearly there are modern (and futuristic!) parts of Dreamland, and it could be fun to set games and stories there. Here’s some thoughts of how to do it while keeping a Dreamlandy feel.

Weird Technology & Artifacts

In Chaosium’s “Dreamlands” supplement for Call of Cthulhu, it’s stated that only technology 500 years old or older can exist there, and that when dreamed into existence, modern things transform into ancient-world equivalents. But this rule seems less intended to preserve a mood, and more intended to keep ’80s RPGers from unbalancing the game by conjuring up machine guns. In Dreamland: Fairytale Portal Fantasy Beyond the Wall of Sleep this Chaosium rule doesn’t apply, and the decision of how much high-tech stuff to put in the setting is entirely up to each individual campaign. Depending on how you and your players present them, such technological artifacts might seem rare and ominous; absurd and intentionally incongruous; or as elegant and symbolic as everything else.

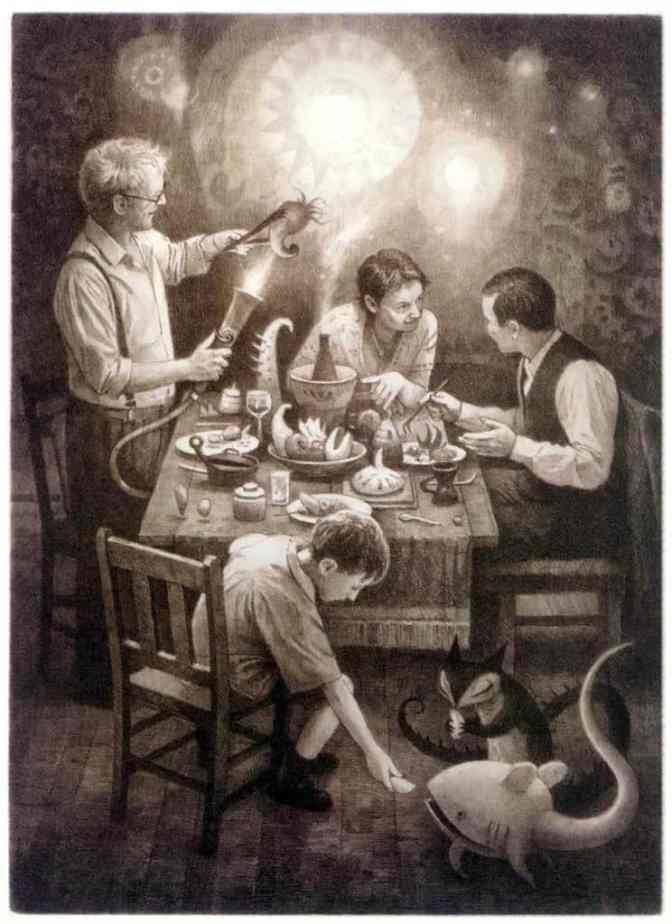

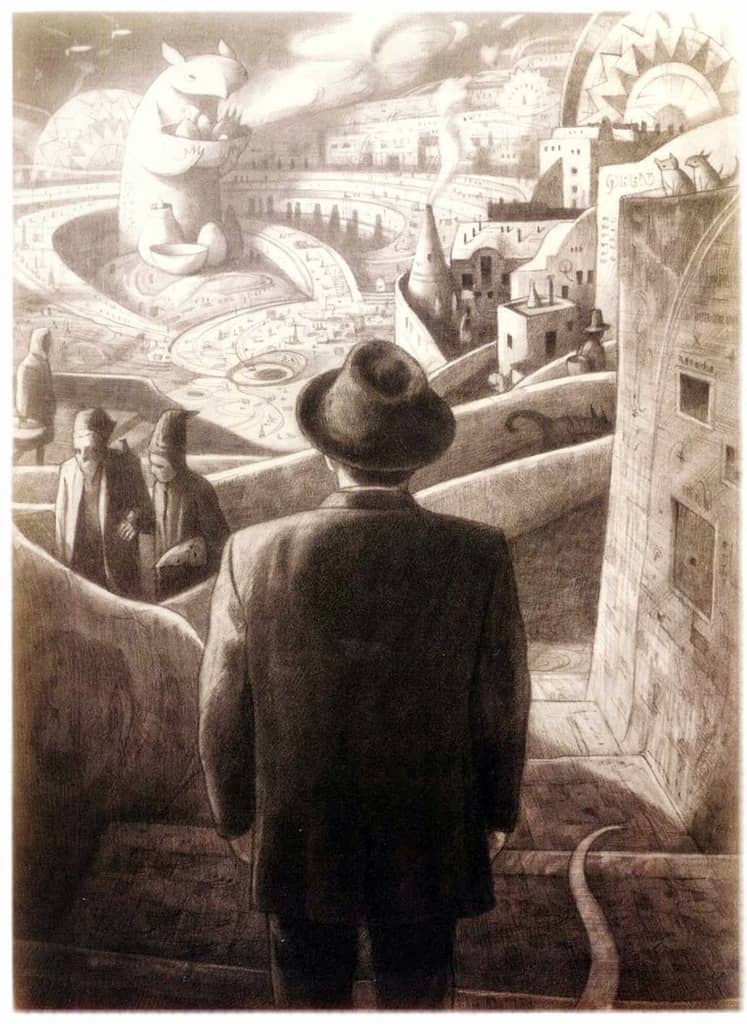

One risk is that familiar technology may make Dreamworld seem too familiar and mundane; but the existence of electric lights and cars doesn’t necessarily make a world less surreal, weird or marvelous. Artist and author Shaun Tan (The Arrival, etc.) is a good example of an author who depicts ‘modern-day’ (or at least 20th-century) worlds which are nonetheless surreal and full of awe. The movies of Alejandro Jodorowsky, especially The Holy Mountain, depict fantasy worlds with quests and magic which also casually contain things such as automobiles, comic books and weapons manufacturers. For a more explicitly science fictional dreamworld, Luka Rejec’s amazing RPG Ultraviolet Grasslands depicts nomadic cultures and faraway cities with strange technology-indistinguishable-from-magic in the style of the comic artist Moebius (himself a frequent collaborator of Jodorowsky). Tim Molloy and Chris Willett’s Painted Wastelands takes a quirkier, more anachronistic approach, with trucks and motorcycle convoys driving Burning Man style through desert cities of monster gods and tentacle-faced wizards.

Even if the average tech level of your Dreamlands campaign is traditionally low, hints and fragments of higher technology may remain. Dreamland is an old place with many layered cultures: perhaps Dunsany’s lost cities Bethmoora or Zaccarath actually had hovercars and supercomputers. The idea that “a great technological civilization destroyed itself and left behind super-awesome weapons”, a la Final Fantasy VII and Laputa: The Castle in the Sky, can be fun but has become a cliché. Perhaps it’s more interesting—and dreamlike—to imagine a world in which fragments of advanced technology are not coveted but are instead ignored, misunderstood or casually accepted. In such a world, indestructible styrofoam and plastic objects might be repurposed for jewelry or ritual purposes. Great garbage dumps filled with rusting cars and unuseable screens would be a desert you cross, or a dungeon you explore. Castles and forts are built upon what was once viaducts and the overpasses of freeways. And perhaps, a few casual tools—digital watches, electric lights, vending machines (if both Obojima and Painted Wastelands do it, why not?), consoles with ChatGPT—remain useable despite the overall decline of technology, maintained by technophilic guilds, by still-viable satellite networks or electric grids, by priesthoods, by demons, by fairies.

Since dreamers can come from any point in human history, the dreamers’ waking selves might bring their own perspective on technology. If a player chooses to play a dreamer from the Stone Age, the average Medieval city of Dreamland might seem miraculously high-tech (and perhaps the dreamer could return to their waking life to share and replicate the wondrous technologies they have seen). If a player chooses to play a dreamer from the far future, Dreamland might seem even more rustic and distant than it does to 21st-century dreamers; or the dreamer might use marvels to conjure up fabulous technological artifacts from the future which to them is the present day. From a rules perspective, the one caveat is that the magic which allows dreamers to travel to and from Dreamland should remain mysterious and unquantifiable, even in the farthest future and most mystic past of the waking world.

Extreme Cultures

Dreamland is a heightened reality where the weird, mystic and mythic exists, and one way this is expressed is by having cultures that are exaggerated and unreal. Dreamlanders don’t always behave like real people and their beliefs or customs seem bizarre to us. In the Invisible Cities fables of Italo Calvino or the short-short stories of Henri Michaux, these quirky cultures have a fantasy style; but they’re not so far off from that genre of science fiction stories, like Star Trek, where explorers encounter weird what-if cultures on isolated worlds.

A great example is Keiichi Sigsawa’s light novel series (and later anime) Kino’s Journey, in which the world seemingly consists of thousands of different city-states, each with its own defining strangeness. The country where murder is legal. The country obsessed with building a giant tower, Babel-like, reaching into the sky. The country obsessed with gladiatorial battles. The country where everyone wears masks. The country where everyone has the same face. Many of the stories involve strange science, such as the land where everyone has telepathic powers, and as a result each person must live in isolation, tended by robot servants, out of fear of the intimacy that will result from knowing what it is in eachother’s minds. These city-fables are explored by the main character, a traveler on a talking motorcycle who has vowed to spend only three days in each place.

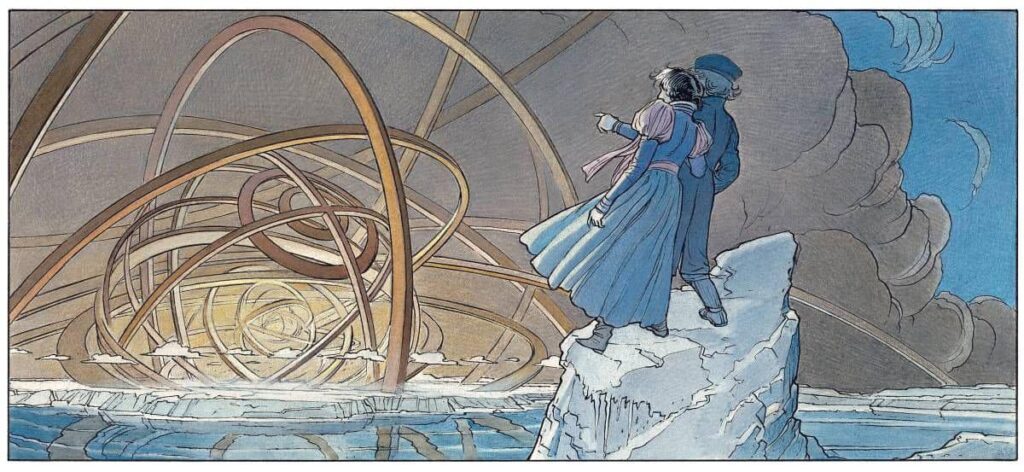

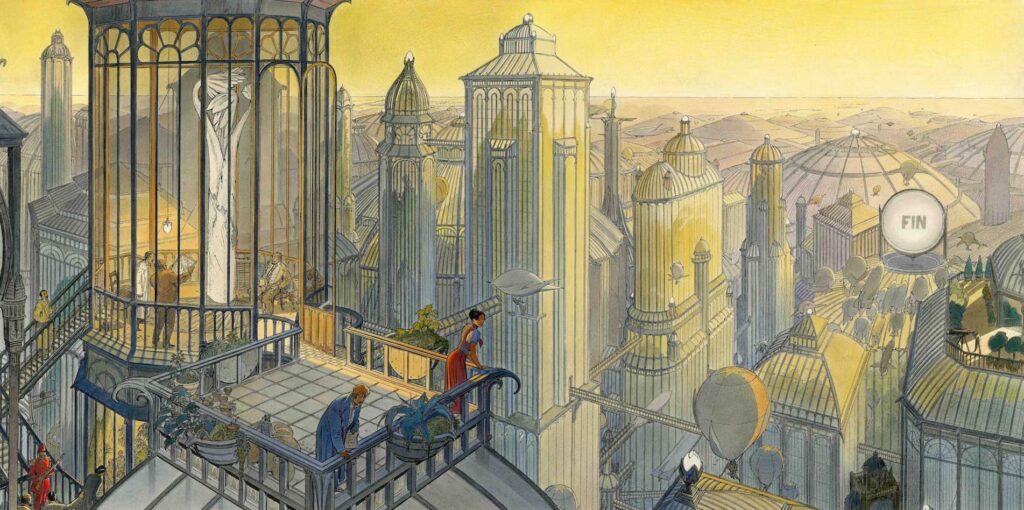

A similar work—but more architectural, befitting the original visual medium of comics—is the world of Francois Schuiten & Benoit Peeter’s The Obscure Cities. These standalone graphic novels each center on a different imaginary city with a different architectural style; but as the series progresses, we find that together they make up a surreal world. “The Tower” is set in a vast Babel-like ruininspired by Piranesi’s drawings. “Samaris” tells of a traveler to a beautiful Belle Epoque city, where he finds that life is governed by illusion. In “Fever in Urbicand,” a technocratic architect’s attempts to build a better planned city are foiled by the appearance of an unearthly phenomenon, a lattice of steel that grows and grows. Other works involve other bizarre cities and reality-bending phenomena, which the people of the Obscure Cities try to study, use and control as best they can: but even in a world of approximately 20th century technology, where humanity can build giant megastructures, there is only so much that humanity can comprehend.

Dreamland cultures might be social satires, organized around any kind of weird bureaucracies or social structure: even the whole-world-is-a-college-campus of John Barth’s Giles Goat-Boy. Any technological dystopia, or utopia, could exist in a single continent or single megacity. On a more mundane note, there’s fun stories to be found in the juxtaposition of modern & ancient societies: not just “fantasy worlds with HR departments,” but things like “laid-off tech workers as wandering ronin roaming the countryside looking for a new master”, “Dreamlanders with credit cards which measure their debt to various ruling feudal entities,” or “the CEO’s many children competing for ownership of the great factory/company their parent once ran.” Looking at the actual neofeudal behavior of some of the richest people in the world in 2025, though, it might be a challenge to create a satire that’s weirder than our current reality.

Isolation and Distance

How do these different weird monocultures with vastly different tech levels coexist in Dreamland? Why don’t bigger cultures just overwhelm and colonize all the others? (well, it must happen occasionally, but…) Because Dreamland is HUGE. Like in Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast, high-tech and low-tech cultures exist on the same flat Earth, unaware of eachother, separated by thousands or millions of miles which only magic—and perhaps dreamers—can cross. Both Dunsany and Lovecraft describe Dreamland Earth as containing impossible cosmological-scale distances (in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, Carter and the nightgaunts seem to fly as fast as “a planet in its orbit” as they zoom over the nigh-infinite mountains towards Kadath, and in The King of Elfland’s Daughter, the Elf King magically expands the distance between Elfland and Earth, to the length of “a space that to cross would weary the comet”). In our waking world, modern physics has the concept of “spacetime”, but in Dreamland, Space—represented by the Pillar of the Faraway—is more than just Time’s lackey.

Some of the core elements of Dreamland are distance, travel and alienation. In a fantasy Dreamland, this might mean the distances of the Silk Road; in a modern Dreamland, it means endless freeways stretching to the horizon, lonely gas stations and rest stops, and unsettlingly identical suburbs. Modern technology might seem to contradict this, with things like cellphones, GPS, social media, etc. But if we rule that literal human teleportation is still impossible or impossibly rare, it’s easy to make workarounds for the other stuff. Christopher Priest’s “Dream Archipelago” series is set in a modern world of apparently infinite islands, where weird time and space distortions make it impossible to completely map the islands (airplanes which fly too high become caught in the time vortex and seem frozen in the air from the perspective of those below). And as everyone who’s studied or used social media knows, the initially freeing effects of such technologies can also lead to a sense of isolation, a feeling that the world is too big and you are alone, like the protagonists in J.G. Ballard’s various apocalypses.

One aspect of modern life is that the city itself becomes not a community but a landscape. Many writers have powerfully depicted cities as dreamlike limbos. In Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren, the vast city of Bellona is perpetually caught between disaster and rebirth; whole blocks are aflame, an unspecified disaster is happening somewhere, there are strange visions in the sky, yet people find places to live and have love affairs and even have dinner parties in the ruins. The seemingly endless, crowded city of Ferenc Karinthy’s Metropole is more of a vision of overpopulation, in line with many 1970s science fiction novels: yet the main character, lost in this busy busy world and unable to learn the incomprehensible language, can only understand a fraction of the life in this seething metropolis as he slowly and painfully runs out of funds. (In Dreamland game terms, if one really had to walk across weeks and weeks of cityscape, you might use Haggling in place of Wilderness for the skill challenge.) On the hellish extreme, you might have nightmare cities of death and decay like the worlds of Alasdair Gray’s Lanark or David Lynch’s Eraserhead.

And then there are landscapes made up entirely of ruins, such as the great garbage dumps which surround Tibor Déry’s G.A. ur X-ben (G.A. in the City of X), or the postapocalyptic wasteland of Mamoru Oshii’s dreamlike anime Angel’s Egg. Although Dreamland is forever expanding (due to the powerful pull of Faraway), technological cultures still have the power to deplete their natural resources and ruin the nearby lands, surrounding themselves with thousands of miles of uncrossable wasteland. In a pessimistic campaign, this might be the fate of all civilizations. But in a heroic Dreamland game, perhaps cities and cultures could resist this fate and triumph over entropy and pollution, or a far-far postapocalyptic future might abandon the urban era and return to pastoralism and small towns, as in Ursula K. LeGuin’s Always Coming Home. If there’s one thing about ‘modern Dreamland’ that I think is most interesting, it’s that Dreamland doesn’t have to be a retro fantasy, and can instead be a way to explore ideas about possible futures as well as imagined pasts. Splatter these possible worlds onto a map, draw lines between them, and there you go.

(art included by Shaun Tan, Francois Schuiten and Kouhaku Kuroboshi)

RECOMMENDED WORKS & CREATORS:

Shaun Tan

Alejandro Jodorowsky, The Holy Mountain

Luka Rejec, Ultraviolet Grasslands

Tim Molloy & Chris Willett, Painted Wastelands

Mamoru Oshii, Angel’s Egg

Martin Bull Gudmunsen & Ole Peder Giaever, Itras By

Ursula K. LeGuin, Always Coming Home

Ferenc Karinthy, Metropole

Samuel Delany, Dhalgren

Tibor Déry, G.A. ur X-ben

J.G. Ballard

Christopher Priest, The Islanders

Mervyn Peake, Gormenghast

Alasdair Gray, Lanark

David Lynch, Eraserhead

Francois Schuiten & Benoit Peeter’s The Obscure Cities

Keiichi Sigsawa, Kino’s Journey