Happy New Year! This article was previously printed in 2012 on mockman.com and is shamelessly reprinted here, with some revisions. It will be part of a series about the inspirations for Dreamland RPG.

“When a man rides a long time through wild regions he feels the desire for a city.”

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Dreamland is a world of cities, and one of its major inspirations is H.P. Lovecraft’s fantasy travelogue, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. H.P. Lovecraft’s stories are filled with descriptions of cities, both fictional and real. From the Nameless City of the Arabian desert built by lizard men, to the marginally more realistic Arkham and Dunwich, to his longest single work, A Description of the Town of Quebec, Lovecraft loved towns and felt — like everyone at some level — that they had an innate existence as more than a cluster of buildings in space. One of his hobbies was antiquarian architecture, examining a town from its streetlamps, its cobblestones, its roofs (gambrel or non-gambrel), its number of fanlights. Cities were his home and hearth, and a way of pinning down the past: a form more visible and intentional than fossils in a riverbed, or the gradual accumulation of topsoil that allows the land to grow grass and trees. As Ken Hite points out in his excellent book “Tour De Lovecraft,” as much as Lovecraft hated urban decay, he was a city boy. Kadath is Randolph Carter’s love letter to his ideal city, filtered through the many other not-quite-ideal cities he encounters on his way (“He swore that Ulthar would be very likely place to dwell in always, were not the memory of a greater sunset city ever goading one on toward unknown perils”). In the same way, Lovecraft wrote a thousand love letters to Providence, from his adolescent poetry to the words I AM PROVIDENCE, from a late letter, now inscribed on his tombstone erected by fans after his death.

Like footprints in the sand of nature, cities stick in the human mind. Julian Jaynes, in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, defines civilization by cities: a civilized person, he says, is someone who lives in a city (or community) too big to personally know everyone else who lives there. Pausanias’ Description of Greece, possibly the first surviving tourist guide, describes cities and shrines but rarely bothers to note natural features; in that age before ecological consciousness the pastoral, with its risk of wolves, weather and highwaymen, was not yet a reason to travel (or maybe in that preindustrial time, there was just so much of it, no one cared?). The earliest travelogues were just lists of cities, names one after the other, like the exotic cities that pass along the river in Lord Dunsany’s “Idle Days on the Yann.” At one time, all roads led to Rome; later, in Medieval maps the city of Jerusalem was drawn at the center of the world, with the continents radiating out from it.

Made-up cities followed real cities; Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi’s A Dictionary of Imaginary Places is full of descriptions of them and their romance, their utopias and dystopias, heavens and hells. Places have souls, as Lovecraft expressed subtly in his best stories, like “Dream-Quest,” and bluntly in his worst, like “The Street.” And people have places where they belong. Even Batman has Gotham City and Superman has Metropolis, which, while they make you wonder where there’s room for the real New York City in the DC Universe, give it a special appeal beyond the idea that Spider-Man might be living on your block.

It was important to Lovecraft not only to describe cities, but to create them. Lovecraft admired the fantasies of Lord Dunsany — they were the #1 inspiration for his dreamlands stories– but one of the many differences between their work is that Dunsany rarely tried to create a consistent mythology. Except for his first book “The Gods of Pegana” and a rare few later linked stories (“Idle Days on the Yann”, “The Avenger of Perdondaris” and “The Shop on Go-By Street”; “Bethmoora” and “The Hashish Man”; “The Distressing Tale of Thangobrind the Jeweler” and “The Bird of the Difficult Eye,” etc.) Dunsany never reused place-names or created a consistent world that could be easily mapped. Most likely, imaginary names came easier to Dunsany, and he just didn’t feel the need to repeat himself. On the other hand, Lovecraft reused everything, like a bird building its nest. As early as “The Quest of Iranon” he’s making references to “The Doom That Came to Sarnath” and “The Green Meadow.” Abdul Alhazred, his childhood Arabian Nights persona, is still appearing as the author of the Necronomicon 40 years later. Lovecraft didn’t have the thoroughness of Tolkien, but he had the same urge to create a single fictional universe that includes everything he wrote — a Grand Unifying Theory, call it the Cthulhu Mythos or Yog-Sothothery or whatever. Dunsany’s cities and creations are like bits of delicate crystal; Lovecraft’s are like stones rounded by frequent handling.

Lovecraft was a homebody — except for his brief stay in New York, all his life he clung to his childhood city, his childhood furniture (what a shame that there are no photographs of it, his ratty old furniture he loved so much he told Helen Sully he’d go insane if he had to part with it!), his childhood home (or as near a simulacrum as possible, since the original house had been sold). But he was also a traveler, spending days on buses and trains, seeing the world as much as his finances allowed (as a California boy, I have to say, it sucks that he never managed to visit Clark Ashton Smith in California), absorbing new sights and memories. Writing about them. And returning home. Home was the axis of the world around which he spun, his reference point that gave his travels meaning and context.

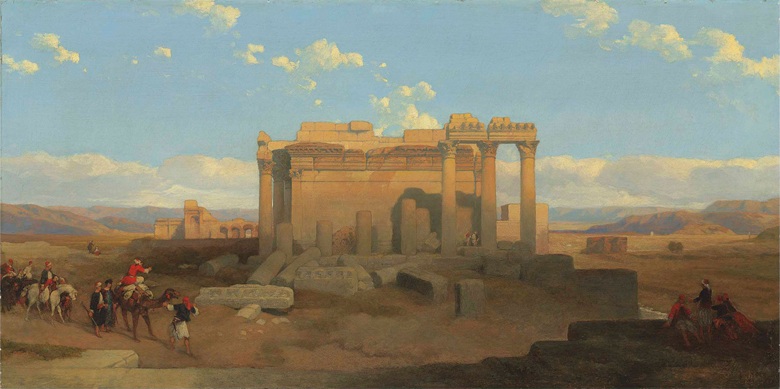

Dream-Quest is the story of a pilgrimage (one of his rejected titles was “A Pilgrim in Dreamland”), a journey to exotic ports from which the hero returns with newfound appreciation of home. It’s inherent in Dream-Quest that Carter and Kuranes are outsiders, tourists, travelers just passing through but not really meant to settle in these fabulous lands (as Kuranes sadly discovers.) We see the dreamlands through the eyes of foreign adventurers, not so much through the eyes of Atal the Little Farm Boy from Ulthar. J. Vernon Shea, as quoted by Ken Hite, says that he thinks one of Lovecraft’s inspirations was 19th century Orientalist travel literature such as the works of Richard F. Burton and Charles Doughty. Late 20th century academics would criticize this narrative of the privileged (white) outsider visiting the East to cherry-pick Enlightenment from the local traditions and return home to write condescending portraits of the natives, but on the scale of racism in Lovecraft’s works, it’s almost sweet of him to write a story in which both the heroes AND villains wear turbans. Marco Polo and Herodotus also returned home after long voyages to write about the Mysterious East, after all, and so did Manjiro, long before imperialism and Elizabeth Gilbert. Every traveler thinks they’re someone special, every traveler is a hero in their own minds. In Orientalism, Edward Said criticizes Western tourist-adventurers in the Middle East for never wanting to settle down and actually participate in the lives of the people (to marry a local, for instance), for always keeping their distance; but like Lovecraft returning to Providence (not to spawn, but to die), these travelers could never sever their ties to Home, to their original mindset and place.

The description of Places Far Away is an exercise for the dreamer as much as for the surveyor, as Italo Calvino proved with his amazing book Invisible Cities, a pastiche of ancient travel literature whose frame story is Marco Polo describing the lands of Asia to Kublai Khan, but whose cities are all allegories, exploring different aspects of the meaning of City, how they are designed, how they are lived in, how they are described. The cities in Dream-Quest and Lovecraft’s other dream-stories are not as aerily conceptual as Calvino’s; even the lands the White Ship passes feel like fantasy RPG settings first (Thalarion is described as a “demon city”! So it must be full of demons!! DEMONS!!!!) and allegories second. Lovecraft, like Calvino or Dunsany, builds his world of cities word by word, but Lovecraft’s vocabulary is almost entirely visual and material. He describes the material that cities are built of; their contents, temples, gardens and houses (sometimes ad infinitum); their color; the experience of walking through the parks and up the hills. He occasionally lapses into E.R. Eddison‘s tedious habit of describing the fabulous jewels and gems that cover everything, as if writing them down added to his book’s value.

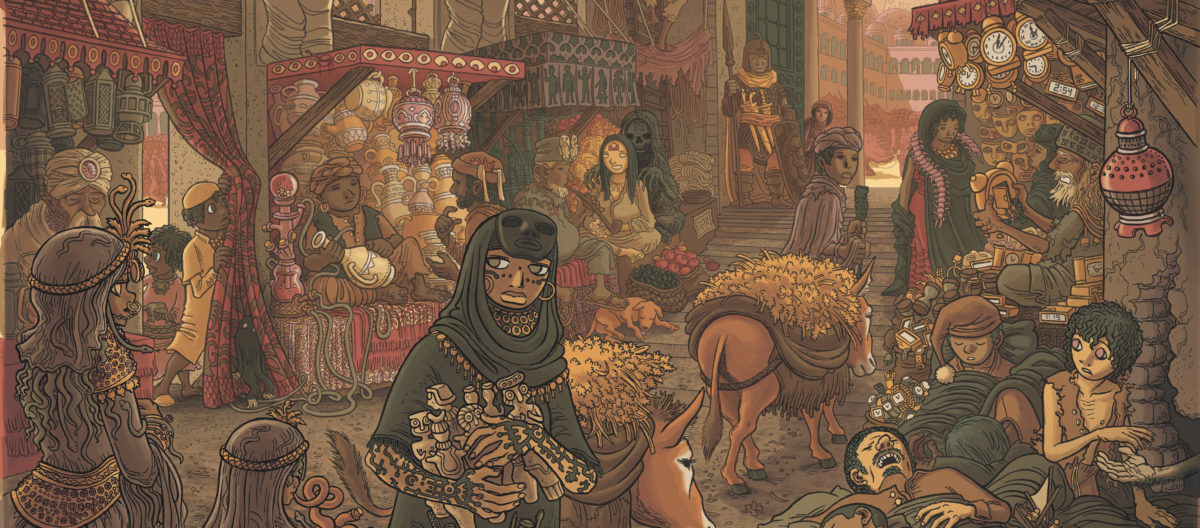

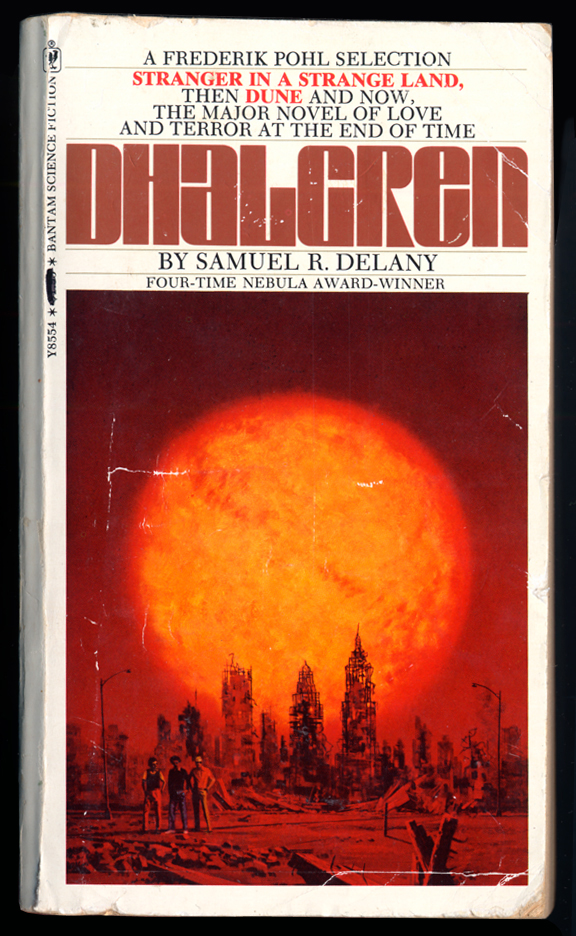

To be blunt, although he enjoys having them in the background, Carter/Lovecraft cares little about the people who built and inhabit these seashell-like cities. (Or who don’t inhabit them; it’s unclear whether the Sunset City is inhabited, and Lovecraft’s ideal of a beautiful East Asian-style landscape, the haunting Gardens of Yin described in Celephais and Fungi from Yuggoth, is a place where there are no people, “but only birds and bees and butterflies.”) Occasionally we hear about the picturesque onxy-miners and sheep-traders, but Carter doesn’t interact with them much beyond asking directions (nearly every single conversation in Dream-Quest) or finding a room at the inn. There’s certainly no aspect of the sexual tourism so often associated with travel, whether Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Martian princesses, or the shivery anticipation (“adventurous expectancy”?) that new places means new people to sleep with, which is such a big part of Samuel Delany’s city-novel Dhalgren and Schuiten and Peeters’ fanservicey Cities of the Fantastic graphic novels and Italo Calvino’s descriptions of innkeepers’ daughters and beautiful odalisques. Carter/Lovecraft has no time for that nonsense (although Lovecraft apparently liked Burroughs when he was younger, and he just felt embarrassed about it when he grew up); he’s in search of a purer beauty. Dream-Quest is a travelogue written by a shy, or simply introverted tourist; Carter interacts more with monsters and cats (a cat to pet in every port) than with people.

Lovecraft’s dreamworld is one of sights and occasionally sounds, but he rarely describes touches or smells, except in a negative context. He’s so unconcerned with physical pleasures that he doesn’t even describe the taste of the food; in “The Doom That Came to Sarnath,” written in his earlier, more decadent phase, Lovecraft goes all-out describing an exotic feast of delicacies, but in “Dream-Quest” Carter hardly eats so much as a bite. Perhaps Lovecraft (who by all accounts had an unadventurous palate on top of not having any money) had, by this time, grown tired of trying foreign food in New York City and resigned himself to a future of eating canned chili and cheese and crackers. Jack Vance and Clark Ashton Smith, those sensualists whose stories of traveling rogues were so much more picaresque than Lovecraft’s “picaresque novel” Dream-Quest ever was, would weep at the missed opportunity.

Given Lovecraft and Dunsany’s love of strange-sounding names (those pins on the map), it’s interesting that the Sunset City in Dream-Quest, the goal of all Randolph Carter’s dreams, has no name. Perhaps this is because it’s Boston and thus to name it would be to spoil the secret, or perhaps, as the Perfect City around which the world revolves, it needs no name. Personally, I’ve suspected that its true name is “Hesperia” (from the Greek word for ‘evening’). There’s no actual evidence for this, but “Hesperia” is the title of stanza XIII of Lovecraft’s Fungi from Yuggoth, which describes a tantalizingly unvisited city beautiful in the light of “winter sunsets,” and it was also the name of a zine Lovecraft once planned to make. Fungi from Yuggoth has other reworkings of imagery which originally appeared in the unpublished Dream-Quest, such as Azathoth, Nyarlathotep and the Plateau of Leng, so perhaps Hesperia is another holdover.

In any case, its name is its meaning: the Sunset City. Why sunsets? Peter Cannon wrote a whole essay about it, Sunset Terrace Imagery in Lovecraft, which I haven’t read. Colin Wilson, in his book A Criminal History of Mankind (the kind of sociological-psychological pop stuff he wrote when he wasn’t writing stories about the Lloigor), proposed that the emotional reaction to seeing a beautiful place from a high vista is derived from primitive hunter-gatherers’ pleasure at seeing new pastures where tasty grazing animals might roam. “We think we feel it in the heart, but it may be in the stomach,” Wilson writes. Is the pleasure in seeing the world, in seeing the landscape from high vistas, simply a kind of biophilia? Lovecraft’s most lovely, most human cities always contain some natural element: Kadath is an icy palace, Teloth is a bleak modern city of gray stone blocks, but the sunset city has its gardens and “grassy cobbles.” Lovecraft’s English-garden vision (or Chinese-garden vision) of an orderly nature, or at least pleasantly arrested decay, is very different from Lord Dunsany’s proto-environmental hate of cities and his love of fields and forests for their own sake. (Tolkien, too, had more love of nature; when I think of Middle-Earth I think of the whole place, of rolling fields and mountains, not of its admittedly nicely described cities.) But then, Dunsany was a rich man with an estate, and Lovecraft, like most people, only had his native streets to wander through.

Perhaps it’s also natural that sunsets make people think of the past, of the remains of the day, of what could have been. It’s probably pointless to overanalyze this: I’m reminded of a Peanuts strip where Charlie Brown tells Psychiatrist Lucy that he prefers sunsets to sunrises and Lucy throws up her hands in exasperation: “What a disappointment! People who prefer sunsets are dreamers! They always give up! They always look back instead of forward! I just might have known you weren’t a sunrise person! Sunrisers are go-getters! They have ambition and drive! Give me a person who likes a sunrise every time!” One of the pleasures of living in a city is the late afternoons, the way the light carves out the shapes of the buildings and the colors change to pinks and blues. On his many bus rides to places along the East Coast, Lovecraft must have seen thousands of sunsets, looking out the window of the rattling bus after the light became too dim to write or read. He saw New York City for the first time in the light of a sunset. There is that moment sometimes when the orange light seems to inflame the whole world, when Sunset’s Gate seems about to open and you could step through to whatever waits beyond. There’s an old anime and manga cliché dating way back to the ’60s or ’70s, in which characters — usually young, hopeful characters like aspiring soccer champions or something — race across a grassy field towards the sunset, to see who can get there first. In the end, as the sun goes below the horizon still un-caught, they stop and rest, lying in the grass, happy and exhausted, ready to go home and get some dinner and sleep. Or maybe the scene fades out with them still chasing their dream. To continue Wilson’s evolutionary hypothesis, perhaps sunset triggers an instinctive urge in diurnal creatures to return home, to seek shelter and sleep. On the most crass level, heartwarming images of houses seen by sunset are just part of the human emotional spectrum, packed and sold in motivational calendars and Thomas Kinkade paintings and other pop trash.

“How often we have seen that City of Never!” wrote Lord Dunsany. “Not when it is night in the World, and we can see no further than the stars; not when the sun is shining where we dwell, dazzling our eyes; but when the sun has set on some stormy days, all at once repentant at evening, and those glittering cliffs reveal themselves which we almost take to be clouds, and it is twilight with us as it is for ever with them, then on their gleaming summits we see those golden domes that overpeer the edges of the World and seem to dance with dignity and calm in that gentle light of evening that is Wonder’s native haunt. Then does the City of Never, unvisited and afar, look long at her sister the World.”

In Dream-Quest, the ultimate unattainable city turns out to be the glorified image of the narrator’s hometown, “moulded, crystallized and polished by years of memory and of dreaming.” When I first read Dream-Quest at the age of 13 or so, I found the ending kind of a letdown, because I didn’t want the Sunset City to be Boston. I wanted less New England; I wanted MORE alienage, MORE wonder, MORE exotic fantasy. But eventually, I grew to appreciate the poignancy of this message, and its appreciation that memories and observed realities are important, that past experiences are the building material of great things. Still, it leaves me wanting more: surely, when we seek the Unknown, we’re not always just wanting to be home again, with a candle at the window, a warm supper, a familiar face? I don’t think that all travels return to the same place; I do think it’s possible to end up somewhere (or someone) different, not just to go back to Square One saying “There’s no place like home” or “It was just a dream.”

But that would be a different story. Maybe Lovecraft could have carried a piece of Providence with him anywhere, even had his physical body lived in Chicago, or Florida, or New York. Luckily for us, he did leave a piece of his ideal city behind; in his writing. And today, armchair adventurers can still look back on these fabulous places retreating ever farther back in time, on old-time Providence, and Quebec, and Arkham, and Kadath.

NEXT: More posts on Dreamland’s game mechanics and contents, as well as on authors who inspired Dreamland.